Library Calling in C

Published: Last Updated:

In this post we are exploring how different types of binaries are generated, how function calls work when code is split across multiple files, and how the toolchain (compiler, linker, loader) helps. We’ll also cover how to build and install a custom libc for testing and debugging purposes.

File Types and High-Level Flow

Difference in types of files:

.c/.cpp: source files.o: object files (compiled but not yet linked).a: static library (archive of.ofiles).so: shared library (dynamically linked at runtime)

Typical build pipeline:

- Compile each source file independently

gcc -c main.c -o main.ogcc -c lib.c -o lib.o

- Link the object files together into an executable

gcc main.o lib.o -o myprog

- Optionally, some of the code may instead be linked from

.aor.sorather than local.ofiles.

At the C level you just write foo(); and include the right headers. The compiler only needs to know the prototype of foo. The actual address of foo is resolved later by the linker (for static linking) or the dynamic loader (for shared libraries).

Setup: Splitting Code Across Files

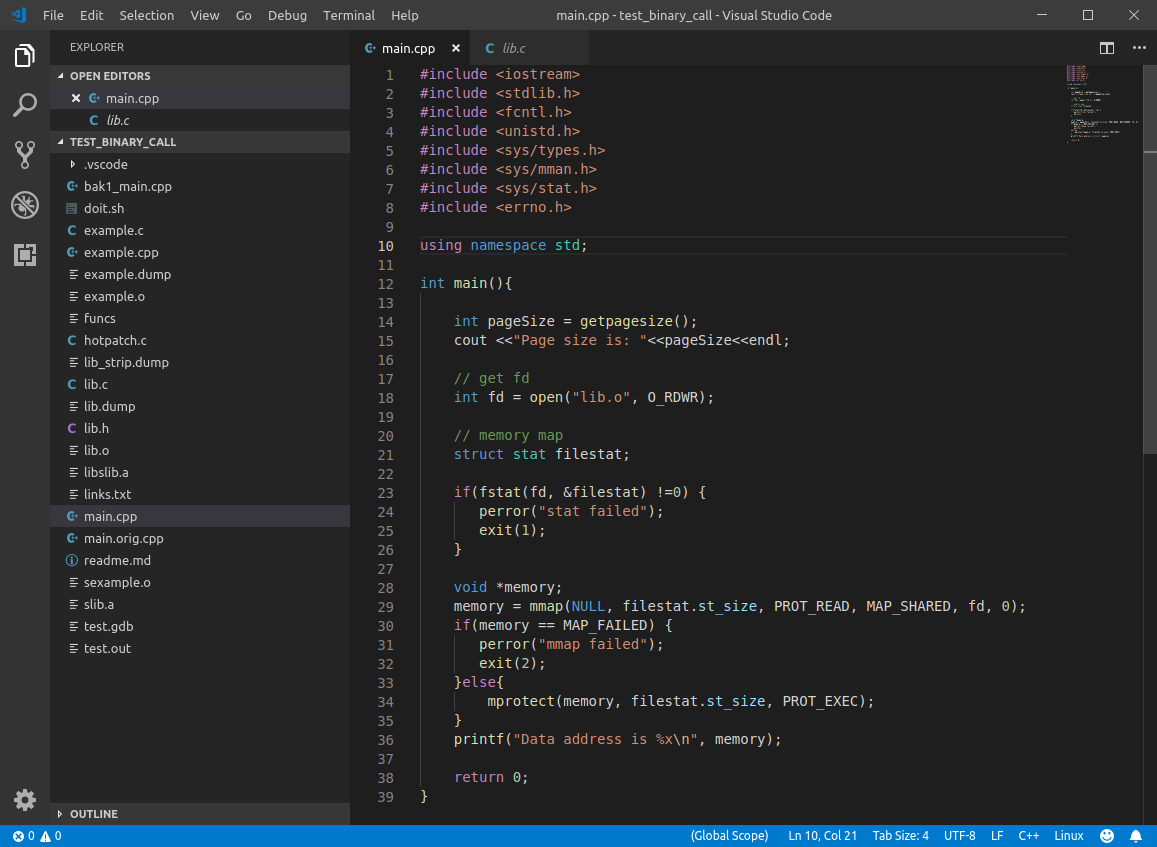

We have our simple main.cpp file:

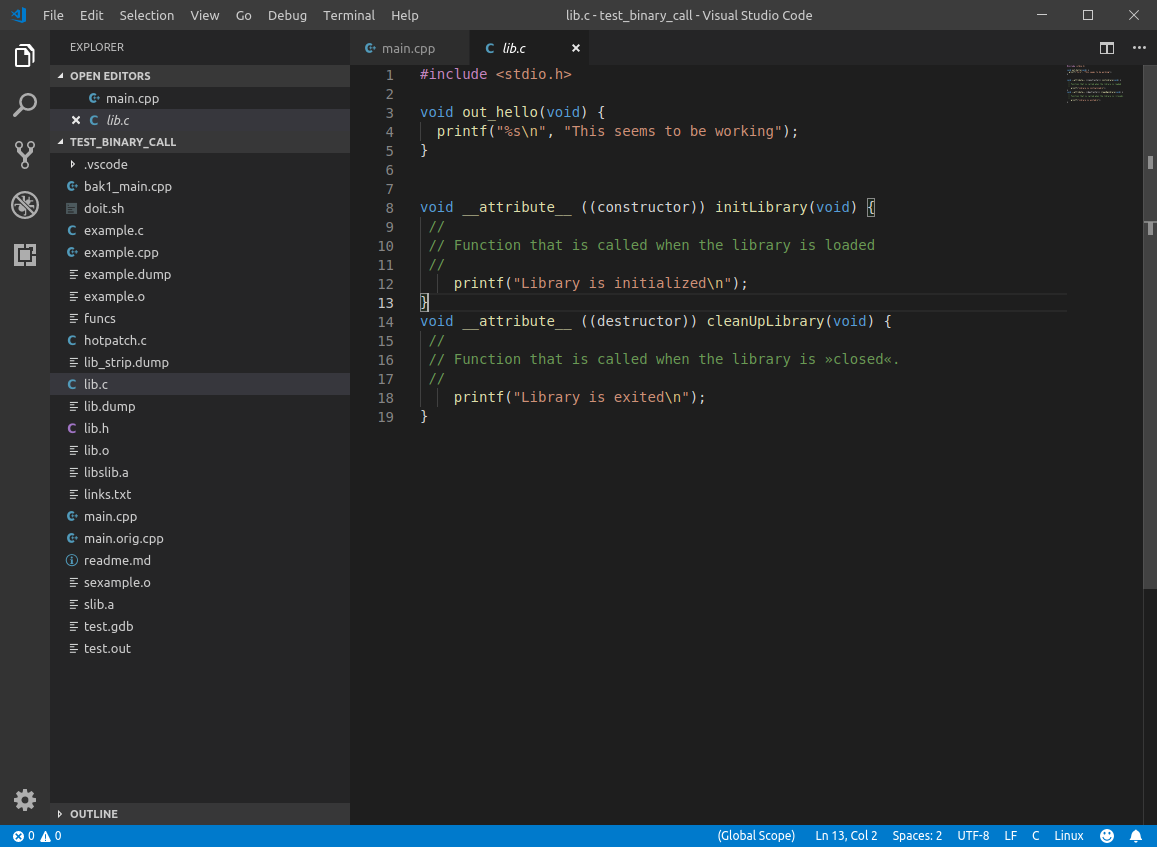

and we have a small library called lib.cpp:

lib.cpp defines some helper functions (for example out_hello()), but it does not define main. If we try:

gcc lib.c

the linker complains that there is no entry point (main).

Instead we compile lib.c without linking:

gcc -c lib.c -o lib.o

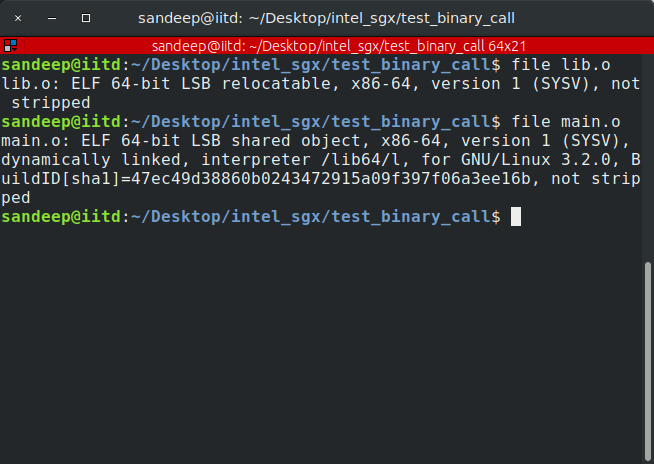

This tells the compiler to stop after generating the object file and to skip the final link step. Different commands produce different file types, as reported by Linux via file:

lib.ois a relocatable object file (can be placed anywhere in memory).main.o(after linking) is a dynamically linked executable.

Our aim is to call the function out_hello which is present in lib.o from main.o. To understand what is happening underneath, we will also use GDB to explore the object files and mappings.

GDB tools

A complete tutorial can be found here https://www.tutorialspoint.com/gnu_debugger/index.htm

The important point is to compile the binary using the -g parameter so that the debug symbols are present in the binary.

g++ main.cpp -g -o main.o

As can be seen in the main.cpp

// memory map

struct stat filestat;

if(fstat(fd, &filestat) !=0) {

perror("stat failed");

exit(1);

}

void *memory;

memory = mmap(NULL, filestat.st_size, PROT_READ, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

if(memory == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("mmap failed");

exit(2);

}else{

mprotect(memory, filestat.st_size, PROT_EXEC);

}

printf("Data address is %x\n", memory);

The code loads lib.o in the memory using mmap and then marks it as protected so that it can be executed. Due to security measures to prevent code injection attacks, an executable memory has to be marked read-only or protected before it can be executed.

Using GDB, we will let the program execute till the last printf statement which for me is line number 36, halt the code there, and explore the list of the functions available.

gdb

file main.o

b main.cpp:36

info proc mappings

The mappings that are shown are:

| Start Addr | End Addr | Size | Offset | Objfile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x555555554000 | 0x555555556000 | 0x2000 | 0x0 | /home/sandeep/Desktop/intel_sgx/test_binary_call/main.o |

| 0x555555755000 | 0x555555756000 | 0x1000 | 0x1000 | /home/sandeep/Desktop/intel_sgx/test_binary_call/main.o |

| 0x555555756000 | 0x555555757000 | 0x1000 | 0x2000 | /home/sandeep/Desktop/intel_sgx/test_binary_call/main.o |

| 0x555555757000 | 0x555555778000 | 0x21000 | 0x0 | [heap] |

| 0x7ffff70a5000 | 0x7ffff70bc000 | 0x17000 | 0x0 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 |

| 0x7ffff70bc000 | 0x7ffff72bb000 | 0x1ff000 | 0x17000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 |

| 0x7ffff72bb000 | 0x7ffff72bc000 | 0x1000 | 0x16000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 |

| 0x7ffff72bc000 | 0x7ffff72bd000 | 0x1000 | 0x17000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 |

| 0x7ffff72bd000 | 0x7ffff745a000 | 0x19d000 | 0x0 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff745a000 | 0x7ffff7659000 | 0x1ff000 | 0x19d000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff7659000 | 0x7ffff765a000 | 0x1000 | 0x19c000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff765a000 | 0x7ffff765b000 | 0x1000 | 0x19d000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff765b000 | 0x7ffff7842000 | 0x1e7000 | 0x0 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff7842000 | 0x7ffff7a42000 | 0x200000 | 0x1e7000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff7a42000 | 0x7ffff7a46000 | 0x4000 | 0x1e7000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff7a46000 | 0x7ffff7a48000 | 0x2000 | 0x1eb000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff7a48000 | 0x7ffff7a4c000 | 0x4000 | 0x0 | |

| 0x7ffff7a4c000 | 0x7ffff7bc5000 | 0x179000 | 0x0 | /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.25 |

| 0x7ffff7bc5000 | 0x7ffff7dc5000 | 0x200000 | 0x179000 | /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.25 |

| 0x7ffff7dc5000 | 0x7ffff7dcf000 | 0xa000 | 0x179000 | /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.25 |

| 0x7ffff7dcf000 | 0x7ffff7dd1000 | 0x2000 | 0x183000 | /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.25 |

| 0x7ffff7dd1000 | 0x7ffff7dd5000 | 0x4000 | 0x0 | |

| 0x7ffff7dd5000 | 0x7ffff7dfc000 | 0x27000 | 0x0 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff7fcb000 | 0x7ffff7fd1000 | 0x6000 | 0x0 | |

| 0x7ffff7ff6000 | 0x7ffff7ff7000 | 0x1000 | 0x0 | /home/sandeep/Desktop/intel_sgx/test_binary_call/lib.o |

| 0x7ffff7ff7000 | 0x7ffff7ffa000 | 0x3000 | 0x0 | [vvar] |

| 0x7ffff7ffa000 | 0x7ffff7ffc000 | 0x2000 | 0x0 | [vdso] |

| 0x7ffff7ffc000 | 0x7ffff7ffd000 | 0x1000 | 0x27000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff7ffd000 | 0x7ffff7ffe000 | 0x1000 | 0x28000 | /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so |

| 0x7ffff7ffe000 | 0x7ffff7fff000 | 0x1000 | 0x0 | |

| 0x7ffffffdd000 | 0x7ffffffff000 | 0x22000 | 0x0 | [stack] |

| 0xffffffffff600000 | 0xffffffffff601000 | 0x1000 | 0x0 | [vsyscall] |

We can see that our lib.o is a mapped function in the binary.

This can be combined in a single line:

gdb --batch --command=test.gdb

Calling the function

Now, we have mapped it. We need to call this. That is a little tricky and there are multiple ways to do that:

Option 1

Link the library with the binary and create a single object file which is capable of running and calling the functions present in the library.Option 2

In this case the main function and the library functions remain in separate files. The main can call the function required for its operation.

Option 1: Statically compiled libraries

The basic idea here is to call a function defined in some other binary (acting as a library) from our sample application.

gcc -c example.c -o example.o

gcc -c lib.c -fPIC -o lib.o

ar rcs libslib.a lib.o

gcc example.o -L. -lslib -o sexample.o

./sexample.o

Option 2: Dynamically calling the library

This is done via using LD_PRELOAD option. Details later in the post.

Building and Installing Custom LibC

Glibc is the standard library that is linked against all Linux applications. It provides the necessary functionality like printf and wrappers for most used system calls like open, read, write, close.

Why Build Custom LibC?

Building a custom libc is useful for:

- Testing new features or patches

- Debugging libc internals

- Understanding how standard library functions work

- Experimenting with performance optimizations

Manual Build and Installation

Example based on a StackOverflow answer:

export glibc_install="$(pwd)/glibc/build/install"

git clone git://sourceware.org/git/glibc.git

cd glibc

git checkout glibc-2.28

mkdir build

cd build

../configure --prefix "$glibc_install"

make

make install

Testing Custom LibC

Create a test C program to verify the custom libc is being used:

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <assert.h>

#include <gnu/libc-version.h>

#include <stdatomic.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <threads.h>

atomic_int acnt;

int cnt;

int f(void* thr_data) {

for(int n = 0; n < 1000; ++n) {

++cnt;

++acnt;

}

return 0;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

/* Basic library version check. */

printf("gnu_get_libc_version() = %s\n", gnu_get_libc_version());

/* Exercise thrd_create from -pthread,

* which is not present in glibc 2.27 in Ubuntu 18.04.

* https://stackoverflow.com/questions/56810/how-do-i-start-threads-in-plain-c/52453291#52453291 */

thrd_t thr[10];

for(int n = 0; n < 10; ++n)

thrd_create(&thr[n], f, NULL);

for(int n = 0; n < 10; ++n)

thrd_join(thr[n], NULL);

printf("The atomic counter is %u\n", acnt);

printf("The non-atomic counter is %u\n", cnt);

}

Compiling with Custom LibC

Use the following script to compile and link against your custom libc:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -eux

gcc \

-L "${glibc_install}/lib" \

-I "${glibc_install}/include" \

-Wl,--rpath="${glibc_install}/lib" \

-Wl,--dynamic-linker="${glibc_install}/lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2" \

-std=c11 \

-o test_glibc.out \

-v \

test_glibc.c \

-pthread \

;

ldd ./test_glibc.out

./test_glibc.out

Key compiler flags explained:

-Lspecifies the library search path-Ispecifies the include path for headers-Wl,--rpathsets the runtime library search path-Wl,--dynamic-linkerspecifies which dynamic linker to use

Verifying Custom LibC Usage

You can add custom print statements inside the libc source code (e.g., in printf function) to verify that your custom libc is actually being called instead of the system default. After rebuilding and running your test program, you should see your custom debug output.

How Function Calls Work Across Multiple Files

Consider the classic pattern:

// lib.h

void out_hello(void);

// lib.c

#include "lib.h"

void out_hello(void) {

printf("hello\n");

}

// main.c

#include "lib.h"

int main(void) {

out_hello();

return 0;

}

Build steps:

gcc -c lib.c -o lib.o

gcc -c main.c -o main.o

gcc main.o lib.o -o app

Key points:

- During compilation of

main.c, the compiler only needs the declarationvoid out_hello(void);. It generates a call to an as-yet-unknown symbolout_hello. - During linking, the linker scans all object files and libraries. It sees that

out_hellois defined inlib.oand patches the call site inmain.oto point to the right address. - If

out_hellolives in a shared library (libfoo.so), the executable contains a reference via the PLT/GOT (Procedure Linkage Table / Global Offset Table). The real address is filled in lazily at runtime by the dynamic linker.

This separation allows you to recompile only the changed .c files, and to ship libraries independently of the main application.

static inline and Inlining Across Translation Units

When you write helper functions in headers you often see:

static inline int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

Why static inline?

inlinetells the compiler: this function is a good candidate to be inlined (no call/return overhead, body is pasted into the caller).staticgives the function internal linkage — each.cfile that includes the header gets its own private copy of the function. This avoids multiple-definition linker errors.

Without static, putting a non-inline function definition in a header and including it in many .c files would cause multiple symbol definitions at link time.

Inlining is purely a compiler optimization decision; using inline is a hint, not a guarantee. The compiler can still choose not to inline if it thinks it will bloat the code too much or hurt performance.

Compiler Optimization Opportunities

Some of the common optimization levels:

-O0: no optimizations, best for debugging-O1,-O2,-O3: increasing levels of optimization-Os: optimize for size-Ofast: more aggressive than-O3(may break strict standards compliance)

With optimizations enabled, the compiler can:

- Inline small functions and remove call overhead

- Remove dead code and unused variables

- Constant-fold expressions at compile time

- Reorder instructions to hide latency

- Vectorize loops (use SIMD instructions)

Example build:

gcc -O2 -g main.c lib.c -o app

You still get debug info (-g) while taking advantage of decent optimizations.

Link Time Optimization (-flto)

Normally, each .c file is optimized in isolation. With Link Time Optimization (LTO), the compiler keeps an intermediate representation and lets the linker run whole-program optimizations.

Basic usage:

gcc -O2 -flto -c main.c -o main.o

gcc -O2 -flto -c lib.c -o lib.o

gcc -O2 -flto main.o lib.o -o app

What you gain:

- The optimizer can see across translation units

- Unused functions in libraries can be completely removed (dead-stripping)

- More inlining opportunities across

.cfile boundaries - Better constant propagation and devirtualization

Downsides:

- Longer build times

- More complex debug experience (optimized code reordering)

For libraries built with LTO, you typically need to enable -flto both when building the library and when linking the final executable.

i-cache Impact and Function Layout

Instruction cache (I-cache) size and layout can have a real performance impact:

- Many small, rarely executed helper functions scattered around can hurt locality.

- Over-aggressive inlining can bloat hot code paths so much that they no longer fit well in the I-cache.

Some practical considerations:

- Inline only truly hot, small functions; leave cold or large functions as normal calls.

- Group related hot code into the same compilation unit where possible.

- Higher optimization levels combined with profiling feedback (PGO) allow the compiler to place hot and cold code more intelligently.

In short, static inline and LTO are powerful tools, but they should be used with an eye on overall code size and I-cache behavior, not just on micro-benchmarks of a single function.

How LD_PRELOAD Works

LD_PRELOAD is an environment variable understood by the dynamic linker (ld-linux.so). It lets you load one or more shared libraries before any other libraries, and override symbols (functions, global variables) from the usual libc or other shared objects.

Example:

LD_PRELOAD=/path/to/mylib.so ./target_program

If mylib.so defines open, malloc, or printf, those definitions will be used instead of the ones in the default libc.

Typical implementation pattern for interposition:

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <dlfcn.h>

#include <stdio.h>

typedef int (*open_t)(const char *pathname, int flags, ...);

int open(const char *pathname, int flags, ...) {

static open_t real_open = NULL;

if (!real_open) {

real_open = (open_t)dlsym(RTLD_NEXT, "open");

}

printf("[hook] open(%s)\n", pathname);

return real_open(pathname, flags);

}

Build as a shared library:

gcc -shared -fPIC hook.c -o hook.so -ldl

LD_PRELOAD=$PWD/hook.so ./some_program

The dynamic linker does roughly:

- Load all

LD_PRELOADlibraries. - Load the program’s DT_NEEDED libraries (like libc).

- When resolving a symbol, search preloaded libraries first, then others.

LD_PRELOAD is extremely powerful for debugging, tracing, or temporarily changing behavior without recompiling the target program.

Putting it all together: functions can live in separate files, static or shared libraries, or even custom libc builds. The combination of declarations, linking, optimizations (static inline, -O2, -flto), and mechanisms like LD_PRELOAD gives you a lot of control over where code runs from and how it is wired up at runtime.